There’s a pervasive myth in America today that real wages have been stagnant for decades.

This idea has been commonplace since at least the early 2010’s, and it’s endlessly repeated by journalists, politicians, and even some economists. Here are a few examples compiled by a couple of great articles looking at this same issue:

Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman wrote in 2014: “Wages for ordinary workers have in fact been stagnant since the 1970s”

NYT Columnist David Leonhardt in 2017: “the very affluent, and only the very affluent, have received significant raises in recent decades”

Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz in 2019: “Some 90 percent have seen their incomes stagnate or decline in the past 30 years”

CNN political analyst Kirsten Powers in 2023: “Late-stage capitalism” is “untethered to morality or decency” and “it’s not working, except for the super-rich”

Joseph Stiglitz again in 2011: “All the growth in recent decades – and more – has gone to those at the top”

All. And more. Not good!

Populist politicians from both sides of the aisle pick up this language and likewise peddle it endlessly. Below is one of countless examples from Bernie Sanders.

And national conservatives such as Oren Cass likewise claim that American workers have suffered from “decades of stagnant wages” and that the “breakdown in American capitalism over the past half-century is most apparent in its failure to deliver widespread prosperity for the American people.”

The idea of stagnant wages drives resentment from both the left and right towards the elite, free markets, and liberalism broadly. Assumed economic stagnation is one of the major fuel sources for economic populism, and the policy implications of this resentment are now becoming painfully obvious.

Young adults in particular hold negative views towards free markets, with 55% having a negative impression of capitalism, compared to only 51% who hold a negative view towards socialism.

But what if the idea that wages have stagnated wasn’t true? What does the data actually say?

Let’s look at data from the U.S. Census Bureau. In 2023, real median household income was $80,610, a full 51% increase in real terms since 1967, the first year that data is available. Clearly, income has not stagnated.

There have been ups and downs since 1967, but overall, the trend is clearly up and to the right. The graph may come as a surprise to many who have spent years listening to politicians and pundits complain about wage stagnation and then call for a dismantling of capitalism, neoliberalism, supply-side economics, or whatever other economic boogeyman they’d like to pick.

The claim that “wages have stagnated for decades” picked up wide usage during the depths of the Great Recession and its subsequent recovery. If you compare the height of real incomes in the late 1980’s to the depths of the recession recovery in 2012, you’ll see real income only increased by ~1%. Based on this single cherry-picked data point, one could claim that wages had not grown “for decades”, but only if you forget about all of the growth before 1989, during the 1990’s, and after 2013.

The longer-term view shows that real incomes have grown considerably and consistently since we’ve measured incomes. Unfortunately, once a negative narrative catches on, it tends to remain lodged in the public’s consciousness much longer than the facts on the ground warrant.

When newer and more positive data emerges, the positive trends are not typically reported on as widely or understood as deeply as the original negative narratives, so the negative narratives continue to drive public opinion and resentment. This “stickiness” of negative narratives is a direct result of negativity bias, and it is a key reason why unwarranted pessimism about markets is so popular.

Are gains being shared by everyone?

Okay, so maybe median income has risen dramatically, but are those gains being enjoyed by everyone? Could it be the case that the rich getting richer is pulling the median higher? The answer is no, that’s not how medians work.

Even so, we can also look at households at each decile to get a sense for how the entire economic spectrum has performed over time. The dark blue median line below is the same as the first graph, showing a 51% real increase since 1967. The income of the 10th percentile household (so poorer than 90% of all U.S. households) has actually grown more than the median, showing that even the poorest Americans are benefitting from real income growth.

The worst performing decile since 1967 is the 40th percentile household, which has only grown 42% in real terms, or 9% less than the median, but still meaningfully positive. While it’s true that the top deciles have gained faster than the bottom deciles, all deciles have still seen meaningful growth. I’ll do another article on inequality before long that looks at this issue in more depth, but for now, the key takeaway is that Americans from across the income spectrum have undeniably benefitted from wage gains over the past 60 years.

Are households the right unit to measure?

Most reports and analyses look at household income rather than individual income over time, so another potential response from skeptics is that the changing nature of American households is skewing the data. Since more families have two working adults today, an increase in household income hides the fact that the income is being generated by two adults instead of just one, right? Once again, the skeptics are wrong.

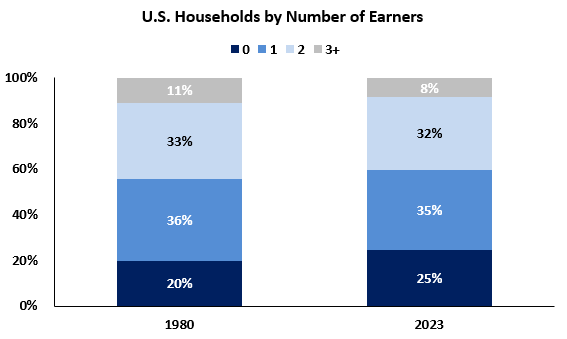

Interestingly, the proportion of households with two earners has actually decreased since 1980, the first year that data on households by earners is available. In 1980, 33% of U.S. households had two income earners, and in 2023, that number had fallen to 32%.

While it’s true that more married couples now are dual-income households, this trend has been more than offset by a declining marriage rate, so overall, the percentage of dual-income households in the U.S. has slightly fallen since 1980.

But that said, the shifting makeup of U.S. households could still be a confounding variable, so what happens when we look at median income on an individual basis? To the dismay of the pessimists, the result is even more income growth. Real median personal income has increased even more than median household income, with real growth of 64% since 1967.

Should we look at income or earnings?

Other doomers might point out that income is too broad a category to look at since it includes non-earned income such as dividends, social security payments, private retirement income, workers’ comp, etc. Solely looking at earnings (wages + benefits) could be better for gauging the financial health of actual workers.

Fair enough, so what happens when we restrict our analysis to just workers? The Census data here only goes back to 1974, but since that time, real median earnings for all workers is up 55%, compared to just 51% for personal income and 37% for household income over the same time period. No matter how you cut the data, consistent earnings growth is the clear takeaway.

Is inflation being counted for correctly?

The Census Bureau data above adjusts for inflation using the consumer price index (CPI), but would another measure be more accurate? The personal consumption expenditures price index (PCE) is another popular measure of inflation, and the PCE is preferred by the Fed.

These two inflation calculation methodologies are similar, but in general, the CPI typically reports higher inflation than the PCE, so if we were to use the PCE for all of the graphs above, the real gains shown would actually be 10-15 percentage points higher than what is currently shown.

The very first graph showing median household income, for example, shows a real median income in 1967 of $53,530. If we use PCE inflation instead of CPI, we get a 1967 real median income of $49,510. Again, not a huge difference, but the real percentage gain through 2023 increases from 51% with CPI to 63% with PCE, or a gain of 12 percentage points. If assumed inflation is higher, then real wage gains are lower, so the CPI-based graphs above are all conservative from an inflation adjustment standpoint.

What about the productivity gap?

Most serious experts will agree that real incomes have risen consistently over the past several decades, but when they claim that wages have stagnated, what they really mean is that wages have stagnated relative to productivity.

This implicit claim is the strongest form of the claim that wages have stagnated, and in a charitable reading of economic populists, this is the claim that they are actually advancing. Of course, large swaths of the public don’t understand the implicit claim and instead have come to believe that real wages have stagnated in absolute terms, which as the prior graphs show, is clearly an incorrect interpretation.

A less charitable reading of the economic populists might assume that their language is intended to mislead – but regardless, addressing the “income-productivity gap” is key to the debate on American wage growth.

The graph below from the progressive Economic Policy Institute is just one of many similar graphs showing a growing wedge between productivity (the amount of production per hour) and compensation per hour. The gap is worrying at first glance. If productivity (dark blue line) is vastly outpacing compensation (light blue line), aren’t workers being taken advantage of?

So, is this graph correct? Unfortunately, the debate over the productivity gap quickly devolves into technical methodological decisions, so the answer is opaque.

AEI has a great report looking at these methodological choices in depth, and after adjusting for things like the types of workers, the inclusion of benefits in compensation, the inflation rate applied to both productivity and compensation, and a productivity measure that accounts for depreciation correctly, you end up with the alternative graph below.

In it, we see that productivity and compensation have tracked each other extremely closely since 1948 when accounted for correctly. The first graph relies on several apples-to-oranges comparisons to incorrectly paint the picture that the productivity gap is large and getting worse.

Reasonable people can disagree about the best way to show the data, and it’s possible that a middle route between the two is most accurate. But crucially, just because the first graph is more commonly seen and drives more political discourse does not mean that it’s more accurate.

The first graph is a news story, while the second graph is not. Due to the stickiness of negative narratives and negativity bias in general, we’d expect the first graph to loom larger in the public’s eye than the second graph, even if the first graph were completely wrong and the second completely right.

So, have US wage gains lagged increases in productivity? Not really, or, if they have, they’ve lagged much less than popular narratives claim. Immigration, automation, and globalization do exert downward pressure on wages, but to say that wages have stagnated over the past 50 years is clearly an overexaggeration.

Conclusion

The idea that American wages have stagnated has become a favorite bipartisan talking point. Populists on both the left and right hammer it constantly. But it’s not just a populist trope – plenty of top economists, policy advisors, and reputable media outlets all parrot the same line too. Can they really all be wrong?

The problem isn’t necessarily that they all got it wrong. The problem is that the data changed, and the narratives didn’t.

Many pundits were technically right (based on cherry-picked data) when they first made comments on stagnation during the Great Recession. The problem is that negative narratives are extremely sticky. If a negative narrative emerges in a given year it will tend to get a lot of coverage. But when the trend reverses, the reversal won’t get nearly as much attention. The bad news goes viral, and the good news, in the best case, gets reported on in esoteric academic journals.

The negative narrative sticks in the public’s consciousness for much longer than warranted. Wage growth is a textbook example. Real wages have grown meaningfully for as long as we’ve had the data, but if you ask most people, they’ll tell you wages are flat. Why? Because that was partially true in 2010, and nobody ever updated their assumptions. To fight these misperceptions, a better understanding of the distorting effects of negativity bias is needed.

The problem of misperceptions has direct policy implications. If people think an issue is worse than it really is, then extreme solutions may be supported when more incremental and moderate solutions would have produced better results. The feeling that things are worse than they are can fuel support for both bad policies and for bad leaders who promise quick, destabilizing solutions to “fix” problems that don’t really exist.

It’s true that wage growth and inequality are key issues that should be focused on. I’m not saying we can just turn a blind eye to these issues, but addressing these issues in the most effective way requires an accurate understanding of the actual issue.

To ensure that policy solutions and the underlying economy are producing maximal outcomes, we first need to weed out false narratives that rely on negativity bias and the stickiness of negative narratives to remain relevant. Doing so will not only improve the public’s perception of capitalism, but it will also allow public officials to focus on the narrow and data-driven policy solutions that will actually improve economic outcomes, rather than chasing nebulous economic or societal boogeyman with destabilizing and extreme solutions.

Even more importantly is what Gale Pooley describes as the time value of money. Here's a great example: https://galepooley.substack.com/p/we-should-measure-prices-in-time.

Here's a calculator he's created: https://galepooley.substack.com/p/try-our-new-time-price-calculator

Because once you start looking at it, you find out that what used to be 'cheap' really isn't, and the lowest 10th percentile is better off today than the 40th percentile or more was just 50 years ago.

Don't mind me re-stacking 1/3 of this post because it's just so damn good and necessary