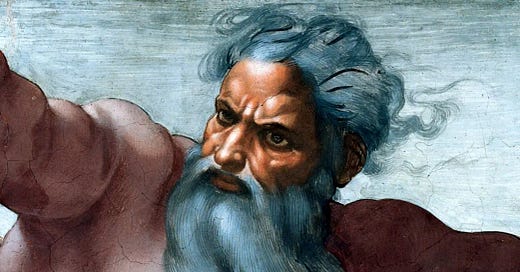

Was Yahweh Invented by Hebrew Nationalists?

And if so, does this pose a problem for Christians?

Robert Wright’s fascinating 2009 book, The Evolution of God has a ton of fascinating arguments, some of which are more convincing than others. Early in the book, Wright raises an interesting question: how was Iron Age Israel able to leave behind the polytheism of its Eastern Mediterranean environment and embrace monotheism, a concept that had no parallel anywhere else at the time?

It’s an interesting question. What allowed monotheism to emerge in Israel, where polytheism or animism had been the norm everywhere else across the ancient world?

Wright argues that the shift to monotheism in ancient Israel was driven by underlying material factors, namely foreign policy and domestic politics, rather than any sort of divine revelation or abstract theological reasoning. If he’s right, this argument could pose an issue for Christians – if materialist causes alone can fully explain monotheism, does that diminish (or negate) the role of divine revelation? And if divine revelation is not the foundation of theology, does theology lose its divine authority and become just another mundane, materialistic ideology?

In this essay I’ll argue that (1) Wright’s initial argument for purely materialistic causes is weak, and (2) even if his materialistic explanation is correct, there are no negative theological repercussions for Christians.

From Polytheism to Monotheism

Wright’s argument for the materialistic and pragmatic drivers of monotheism is fairly common among Biblical scholars. Like many others in this field, Wright begins by explaining why he believes the break between Hebrew monotheists and their contemporary polytheists wasn’t as clean as many imagine. Before there was monotheism, there was likely monolatry.

Whereas monotheism denies the existence of other gods, monolatry acknowledges the existence of other gods but denies that they should be worshipped. The shift to worshipping only one god, rather than many, is often seen as a key step in the progression from polytheism to monotheism. In this understanding, monolatry serves as a kind of waypoint between belief in many gods and belief in one god.

That said, the transition from worshipping many gods to worshipping only one god involves a significant leap, so, how did this massive shift actually come about?

First, some historical background

According to the traditional Biblical narrative as laid out in the Deuteronomistic history of the Old Testament, the Kingdom of Israel was a unified political entity that existed around ~1000 BC first under the reign of King Saul and then, notably, David and Solomon.

The Kingdom of Israel marked the transition of the Israelites from a scattered tribal society ruled by various judges to a unified political entity ruled by a king, as recounted in the books of Samuel.

The emergence of the Kingdom of Israel occurred amidst the power vacuum left by the Bronze Age Collapse (c. 1200 BC). Of the four major Bronze Age eastern Mediterranean great powers, the Mycenaean Greeks and the Anatolian Hittite Empire both completely collapsed during this period, while the Assyrian Empire and the New Kingdom of Egypt both survived in drastically weakened forms. The collapse of these great powers allowed for a unified Israelite state to fill the resulting power vacuum at the beginning of the Iron Age.

The existence of the unified monarchy is a topic of debate within academic circles, with many biblical scholars arguing that the archaeological evidence for an extensive kingdom is too weak to support the claims made by the Old Testament. Regardless of the extent of the unified kingdom, scholars unanimously agree that by c. 900 BC, Israelites lived in two distinct kingdoms – the Kingdom of Israel in the north and the Kingdom of Judah in the south, as shown below.

Zooming back out, the geopolitical situation for both Israelite kingdoms at the beginning of the Iron Age was complex. In addition to being surrounded by minor kingdoms like Edom, Moab, Ammon, and the Phoenician city states, the Israelite Kingdoms were also surrounded by the rising great powers of Egypt to the southwest, the Assyrian Empire to the northeast, and the Babylonians to the East, as shown below.

Each of these three great powers were well on their way to regaining or eclipsing the power they enjoyed towards the end of the Bronze Age, and as their power grew, the crossroads of the Levant became a natural arena for great power competition.

Back to Monolatry

With this foreign policy situation in mind, we return to Wright’s argument for why monolatry evolved from polytheism in Iron Age Israel. To summarize, Wright relies on evidence from both the Old Testament itself and archaeology to argue that Israel was originally polytheistic, much like every other Semitic group at the time. The evolution to monolatry was then caused by two main forces: foreign policy pressures (“FP scenario” for short) and forces related to domestic politics (“DP scenario” for short).

On the foreign policy side, the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah’s precarious position of being surrounded by multiple great powers posed obvious foreign policy threats. To counter these threats, Wright argues, Israelite leaders had an incentive to embrace a strident nationalism that rejected foreign involvement and promoted national unity through a hawkish, isolationist posture.

This “Israel First” approach involved demonizing foreign powers, and Wright uses interesting support from the Old Testament to make the case that this foreign policy posture eventually won out against competing internationalist and pluralistic approaches. Since during this period, national gods like Yahweh acted as a sort of figurehead for the nation, a hawkish posture that involved severing ties with other kingdoms also meant severing ties with foreign gods in favor of Yahweh.

Domestically, a similar incentive existed to downplay the significance of other gods. As the national god, Yahweh’s authority was closely tied to the credibility of Israel’s central government. By elevating Yahweh’s prominence and suppressing the worship of local Yahweh-derivatives or other local deities, the central Israelite government was effectively increasing its own authority and ability to exercise absolute power.

Together, the FP and DP scenarios provide complimentary materialistic explanations for why Israel developed monolatry. In Wright’s view, embracing monolatry was simply in Israel’s national interest.

Wright goes on to explain how this early form of monolatry evolved into the full-fledged monotheism we know today, leaning heavily on the Babylonian Exile for explanatory power. However, for the purposes of this article, I’ll just focus on the first step of getting to monolatry, which Wright attributes to the supposed practical benefits of a heavily nationalist foreign and domestic policy that fostered political centralization and social cohesion.

This materialistic explanation can pose a problem for theists who would rather believe that monotheism was a purely theological development resulting from divine revelation. Wright himself makes this point and argues that a materialistic explanation for monotheism can be a tough pill for Jews and Christians to swallow. So, is he right? Should monotheists be concerned?

My Response

There are several issues I have with both Wright’s initial argument and the implication that the argument poses a problem for monotheists.

First, for pragmatic or materialist explanations to hold, they must account for why the same forces didn’t produce similar outcomes in other similar contexts. For example, why did the Phoenicians or Moabites, who were similarly vulnerable kingdoms pinned between rival great powers, not develop monolatry? If Wright’s FP and DP scenarios are correct, wouldn’t we expect these same materialist forces to drive the emergence of monolatry in other similarly situated kingdoms?

Returning to our map of nearby kingdoms, the Phoenicians, Philistines, Edomites, Moabites, and Arameans all faced foreign policy situations similar to the Israelites, yet each retained their polytheistic beliefs focused on the continued worship of El, Asherah, Baal, Anat, and Mot. This fact poses an obvious issue for the FP scenario.

Perhaps one can argue that foreign policy situations are never truly comparable given different geography, relative military strength, political centralization, and ethnic makeup. Fair enough, there are a lot of variables that make foreign policy comparisons difficult, but the DP scenario suffers from the exact same issue.

Domestically, these nearby kingdoms would have all benefitted from greater centralized control and legitimacy (or at least, their respective kings would have believed so), so the fact that these kingdoms didn’t also tend towards monolatry suggests that the DP scenario isn’t as strong of a force as Wright argues.

If it were, we would expect other nearby kingdoms (or any political entity anywhere on earth, really) to also tend towards monolatry. Instead, we see the opposite: polytheism persisting in other contemporary societies worldwide, regardless of their level of state centralization.

The Babylonian Empire, which ultimately conquered the southern Kingdom of Judah, was highly politically centralized. Although the Babylonians had a national god (Marduk), they never denied the worship of other Babylonian gods such as Enlil, Enki, Inanna, and Nabu, despite Babylon’s clear desire to maintain strict centralized political control over both their homeland and their foreign conquests.

The Roman Republic and early Empire is another great example. Despite being one of the most centralized and efficient state in history, Roman religion was entirely polytheistic for hundreds of years and was generally tolerant of other religions, so long as those other religions were also pluralistic. Rome never developed or tended towards a home-grown monolatry that solely venerated Jupiter or any other singular deity. Eventually, Rome adopted Christianity, but this adoption of an existing monotheistic religion differs fundamentally from Wright’s argument for how a home-grown monotheism could be developed organically.

The lack of widespread monolatry in other societies despite similar circumstances and incentives implies that the FP and DP scenarios aren’t as explanatory as Wright argues. Instead, the move to monolatry can be better thought of as having occurred for another reason, perhaps theological, with these tangential centralization benefits only recognized in hindsight.

Theological Implications for Monotheists

Even if we were to grant that the move to monolatry was purely materialistic, does this pose a problem for monotheists? I’d answer no.

To start, even the argument that ancient Israel was originally polytheistic can be uncomfortable for many Christians. But why should it be? For Christians, there is universal agreement that the Jewish understanding of the messiah prior to Christ was radically different from who Christ turned out to be. In the first centuries after Christ’s death, debates raged within Christendom about the nature of Christ, the Father, the Holy Spirit, and the Trinity. Intra-Christian debates about the nature of God even continue today. If our understanding of God has never been perfect and is continuing to evolve and be debated, wouldn’t we expect to have had an understanding of God that was incomplete and evolving millennia ago as well?

For Jews and Christians, God’s nature is ineffable, so it’s not surprising that our understanding of the nature of God is highly imperfect and changes over time. God’s immutability, or unchanging nature, is a key characteristic of God, but God’s character can be unchanging at the same time as our understanding of God’s character constantly evolves. The two are not mutually exclusive. Therefore, an evolving view of God, even one that incorrectly situated God within a polytheistic pantheon for a time, shouldn’t be a theological problem for Jews or Christians.

Additionally, granting for the sake of argument that Israel really did develop monolatry for purely political reasons, this fact alone has no bearing on the actual truth-claim of God’s existence. Said another way, the means by which Israel came to believe in a single God are a completely separate issue from whether a single God actually exists. Just because Israel developed monolatry for political reasons doesn’t mean that an omniscient and omnipotent God couldn’t have ordained the FP and DP scenarios as tools to guide Israel toward a better understanding of God. So, even if it’s the case that purely materialistic forces explain the rise of monolatry and then monotheism, Jews and Christians shouldn’t lose sleep over it.

This distinction is related to Bulverism, which is a logical fallacy identified by CS Lewis in which an argument is incorrectly rejected because of the background or motive of the argument’s proponent. For example, a skeptic might dismiss Christianity by saying “You only believe in Christianity because you happened to be born in America.” While it may be true that the Christian’s circumstances influenced their belief, this fact is completely separate from the actual truth-claims of Christianity, so the skeptic in this case is wrong to dismiss Christianity on these grounds alone.

Imagine instead that the skeptic states “You only believe in calculus because you learned it in school.” While this statement is true, that the person in question wouldn’t have believed in calculus had they not learned it in school, it in no way undermines the truth of calculus itself. The validity of calculus (or God) exists independently of how people come to know that truth. Similarly, the truth claims of Christianity or Judaism exist independently from the historical process by which those beliefs developed.

In summary, I think Wright’s argument for a purely materialistic explanation of monotheism’s development is weak, but even if his argument is correct, it would pose no theological threat to monotheists. The process through which Israel came to believe in one God – whether through material forces, divine revelation, abstract theological reasoning, or some combination – does not determine the truth of God’s existence. Wright’s argument, while interesting, ultimately fails to undermine the theological foundations of monotheism.

Great analysis and I learned a ton from this! I've come from a Christian backround and have stepped away from the Christian interpretation writ large. I think there's more to the story and you do a great job of highlighting that.

Ironically, Christianity has become polytheistic again with their complexity of the Trinity. The three independent yet inter-related aspects of God.

Following up on your second point — even if the Israelites originally adopted monotheism for political, pragmatic or material reasons, another possible argument that this doesn’t undermine Judaism’s faith is that they have stuck with it despite all the travails they experienced shortly thereafter and ever since, down to the present day. From the destruction of their independent kingdoms, to the Babylonian captivity, their homeland being subject to foreign powers for the next 2,500 years, severe persecution throughout medieval Europe, Russian pogroms, the Holocaust, and the constant hostility and invasions by modern Israel’s neighbors since its founding in 1948.

The Jewish people have obviously been sustained by their monotheistic faith in God throughout all of this, otherwise they would have disposed of it long ago — perhaps as early as the Babylonian captivity c. 600 BC. This speaks to a profound spiritual attachment and belief in their monotheistic faith, and it is doubtful this would exist if the faith of Jews (or Christians) for the past 2,500 years was grounded merely in material concerns.