Why do we care about voter turnout?

Is voter turnout really a predictor of a healthy democracy?

Many Americans, myself included, believe that we should strive for a stronger democracy. The question is, what does a stronger democracy look like? Higher voter turnout? That was my first guess, and that seems to be the first guess of many from both the Left and the Right. After all, higher voter turnout rates lead to better political outcomes, right? Surprisingly, the opposite may be true.

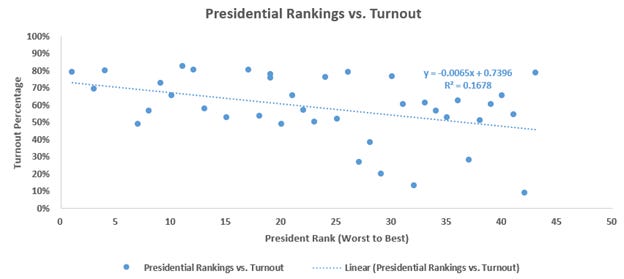

The most obvious relationship that should exist to prove the merit of voter turnout is a positive correlation between voter turnout and the quality of the candidate elected. One would expect that higher voter turnouts would lead to better elected officials.

As the graph below shows, we actually see the opposite. The x-axis is a ranking of each president with 1 being the worst, and the y-axis is each president’s voter turnout as a percentage of eligible voters. As it turns out, there is a negative correlation between voter turnout and the quality of the president elected. You read that right: the higher the voter turnout, the worse the president is.

Sources: United States Elections Project, UCSB’s The American Presidency Project, C-SPAN’s Presidential Historians Survey 2021.

Historically, it has been tough for researchers to show “good” outcomes associated with higher voter turnout because of how subjective politics is. What’s “good” for one side of the aisle might be considered bad by the other. Luckily, once the dust of contemporary politics settles, it typically becomes historical consensus. C-SPAN’s “Presidential Historians Survey”, which drives the data in the graph above, asks dozens of “historians, professors and other professional observers of the presidency” to anonymously rank all of America’s presidents on a series of metrics. The 2021 iteration of the survey had 142 respondents, and although you can certainly debate the subjective nature of presidential rankings, an aggregated ranking of presidents by qualified historians is likely one of the most objective measures of candidate quality that can be found.

Assuming voter turnout is a good thing, we would expect to see a positive correlation between the voter turnout of each president and their respective ranking, but of course, we see the opposite instead. Interestingly, when looking for research that either affirms or contradicts this conclusion, I found that most voter turnout research starts from the assumption that higher voter turnout is beneficial and then looks at ways to increase it, rather than asking whether higher turnout is a net benefit in the first place.

It's certainly true that the R2 of the data is low, but should we really take comfort in the best-case explanation of the above data being that there is no correlation between voter turnout and the quality of the candidate elected? Either way, I think the data, whether it’s a negative correlation or no correlation at all, paints a very dismal picture of the importance of voter turnout.

Of course, if there were no downsides to higher voter turnout, this wouldn’t really be an issue. The downsides, however, are numerous. For starters, there is a statistically meaningful 47% positive correlation between presidential voter turnout and the level of polarization, as shown in the graph below. Historically, the correlation is seen in the Reconstruction era when polarization and voter turnout were both at all-time highs and then again in the early to mid-20th century, when voter turnout fell dramatically and polarization was likewise at its lowest point in U.S. history.

Sources: United States Elections Project, UCSB’s The American Presidency Project, DW-NOMINATE polarization data from Voteview.

1) Polarization scores reflect the widely cited and accepted scores as determined by Poole and Rosenthal’s DW-NOMINATE methodology, which is based on roll call voting in the U.S. Congress beginning in 1879. The scores represent the difference between the Republican and Democratic Party means on the first dimension of their methodology, with higher scores representing more polarization. More information can be found on the methodology at Voteview.com

With voter turnout linked to polarization, it is also linked to the multitude of other negative effects of polarization on both a political and social level, including more political gridlock, negative impacts on mental health, the degradation of interpersonal relationships, the loss of societal trust in neighbors and institutions, etc.

The link between polarization and voter turnout makes a lot of sense, even though it is rarely talked about. Human beings are undeniably and reliably motivated by fear, so it’s no secret that the best way to motivate potential voters is to scare them to the ballot box. These scare tactics, of course, lead to more polarization and misguided fear of the “other side”.

Voter turnout, then, becomes a good predictor of polarization, because a society that is generally in agreement about governance and that doesn’t think their livelihood is on the line come election day will be less likely to vote. On the flip side, constituents who believe the sky is falling, the “other side” is to blame, and the only fix is the government, will be extremely likely to vote.

So, what should we make of this? If voter turnout is better correlated with polarization than positive electoral outcomes, should we really be encouraging it at all? At the very least, we shouldn’t view low voter turnout rates with dismay or high voter turnout rates as a sign of a vibrant democracy. Recently, voter turnout rates have been hitting multi-decade highs, and yet this fact is rarely linked to the fact that polarization is also at multi-decade highs.

One way to decrease polarization, then, is to stop guilting (or scaring) people to the ballot box. If higher voter turnout rates don’t lead to better outcomes, there’s no reason to push for more civic engagement from friends and family members. Many people find politics stressful, tedious, or boring, and that’s okay. We should leave these people alone. If their happiness and wellbeing is better served by not becoming politically engaged, that’s just fine. Guilting (or worse, scaring) these people to the ballot box is not only not leading to better outcomes, but is likely tied to increasing polarization.

Of course, if anyone has information pointing to the positive effects of higher voter turnout on electoral outcomes that I haven’t been able to find, please share with me in the comments. I’m listening. But in the meantime, why do we care so much about voter turnout?