Why does God allow evil? The question is one of the most fundamental issues in theology. It's also one of the most powerful challenges to a good, omnipotent God. If God were good and all-powerful, wouldn't he prevent evil? Since we see evil, doesn't that mean that God is either not good, not powerful, or simply nonexistent?

Philosophers and theologians have responded with various defenses and theodicies for millennia, but for many, these responses have remained unconvincing.

To vastly oversimplify, some of the most popular responses to the problem of evil have included:

The free will defense, in which God allows for humans to have free will, which necessarily includes the freedom to do evil

The soul-making theodicy, in which evil is necessary for the betterment of individuals, such as the fact that the virtue of courage requires the evil of fear to be possible

Skeptical theism, in which God’s designs are ultimately unknowable to us, so what might seem bad in the moment may actually be part of "God's plan"

These arguments may seem compelling at first, but the strongest form of the problem of evil preempts these popular responses fairly easily. In agnostic

’s viral Jubilee debate against 25 Christians, the first topic tackled was the Problem of Evil.Not surprising, given the difficulty Christians have in responding to this argument. Notably, Alex jumps right into the strongest form of the argument:

“We look at the world and we see … a system of natural selection – the mechanism by which God apparently chose to bring animals and ultimately human beings into existence – a system which is defined by suffering, survival of the fittest, which is the same thing as the death and suffering and destruction of the unfit.

I’m told that the very mechanism that God chose to bring about the human species as the ultimate end of His creation was one that is imbued with suffering, such that 99.9% of all the species, let alone animals, that have ever existed on planet Earth have been brutally wiped from existence…”

It's a strong claim. 99.9% of all species, let alone animals, have had an existence almost solely defined by suffering and eventual extinction. The first Christian debater struggles to respond and is quickly voted off the stage. The second debater then asks what aspect of suffering Alex is honing in on. He responds:

“In particular, non-human animal suffering, because I think that Christianity has a celebrated tradition of theodicies trying to explain why suffering exists: human free will, the development of the soul, higher order goods, all of this kind of stuff, none of which applies to the suffering of non-human animals.”

So there you have it, the strongest form of the problem of evil: the problem of non-human animal suffering. Alex sums up the question well just a few moments later, when he asks “What kind of God are we imagining that would allow and oversee and do nothing to prevent billions of years of untold animal suffering?”

It’s a tough question, and one that frankly none of the Christians on the show answered very effectively. Granted, it was a tough format with just a few minutes for each of them to respond, but still, the problem is undoubtedly extremely difficult.

For hundreds of millions of years before humans existed, countless animals experienced predation, disease, starvation, and extinction. In this context, the free will defense is meaningless without humans around to exercise free will. Soul-making is likewise unworkable since animals are not being formed into morally perfected beings through their pain. Skeptical theism makes little sense on the timescale of hundreds of millions of years, not to mention its many other issues, many of which are raised by other Christians.

If the most popular traditional responses to the problem of evil aren’t very effective when viewed in this context, what are we left with? Pre-human animal suffering seems gratuitous, purposeless, and theologically silent. It matches perfectly with a naturalistic or indifferent universe. Why, then, would a good God permit such a long history of apparently meaningless suffering?

The Eternal Weight of Glory Defense

2 Corinthians 4:17: "For this light momentary affliction is preparing for us an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison."

Romans 8:15: “For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is going to be revealed to us.”

What if, in light of eternity, suffering becomes metaphysically insignificant? The defense I advance in this essay is rooted in the eternal destiny of conscious beings, and it draws from Scripture, reason, and practical ethics to show how the problem of evil loses its force when framed within the infinite nature of divine redemption.

We begin with the standard Christian claim: God is omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent. God's ultimate purpose in creation is to bring rational creatures into eternal communion with Himself. From this perspective, temporal life is not the final state. Instead, temporal life is just a prelude to eternity.

If this is true, then we must evaluate earthly suffering in the context of infinite conscious existence. If eternal life is granted to all sentient beings (or at least made freely available to all humans), then any finite amount of suffering shrinks to near-zero significance when viewed on the scale of eternity.

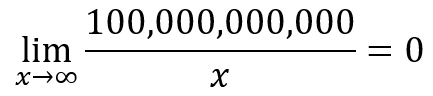

Let’s suppose that 100 billion units of suffering have occurred throughout history. Now assume that each person and sentient creature receives eternal life. What percentage of both their individual and collective existence will be marked by suffering?

Mathematically, the answer is zero:

Suffering is real, but ultimately, it’s completely insignificant. Any finite amount of suffering, even the sum total of all sentient suffering in history, is mathematically zero when compared to eternity.

Importantly, eternal life is not a reward in the sense of simply outweighing past evils. It is not, for example, as if I lost $10,000 one day and then gained $50,000 the next day to make up for it. Instead, the nature of eternity means that it’s as if I had never lost the $10,000 in the first place.

Back to the Alex O’Connor debate, the closest someone gets to an argument like this comes about 10 minutes in. One debater is arguing that God could give animals a praiseworthy status in the afterlife that redeems them for past suffering.

Alex dismisses this approach:

“God might cause them to suffer a bunch and then essentially redeem them in the afterlife, but what for? Why do this? If I were to punch you in the face and then give you $20,000 afterwards you might be grateful for the $20,000, but why couldn’t I just give you the $20,000?”

Alex commits a massive categorization error here. The afterlife is not a finite reward for finite suffering, it is an infinite reward for finite suffering, which necessarily means the finite suffering is completely insignificant.

Could one still ask why God needed to create suffering, even in light of its insignificance? Sure, but I can’t write enough words here to describe just how insignificant this question is in light of eternity. It’d be like asking why God chose to create a single specific grain of sand on a beach in Thailand, or why God chose to create a single specific hydrogen atom on the sun. One can ask these questions, but quite literally, they could not be any less significant.

Of course, pain and suffering feel significant in the moment. I’m fully aware that this approach feels abstract and removed from real suffering, but the point of this article is to provide a narrow response to an abstract critique of theism. For people who are abstractly pondering the reasons for pre-human animal suffering, this response is appropriate. For others who are seeking answers for the immense suffering in their own lives, other pastoral resources would be much more effective.

This defense is also not a hand-waving dismissal of suffering. Instead, this defense is a metaphysical contextualization. Suffering is real, but when weighed against infinite joy, peace, and divine presence, it becomes an infinitesimal sliver of a much greater whole.

Do Animals Go to Heaven?

The Eternalist defense requires the belief that all sentient creatures, past and present, will share in eternal life. Without this belief, the problem of pre-human animal suffering still exists. But, assuming that all sentient creatures are fully restored and share in eternal glory, the mathematical reality of every animal’s earthly suffering is reduced to zero.

So, what is the Biblical basis for resurrected animals? Christian theology has historically been somewhat quiet on animals in heaven, but despite the lack of focus on this topic, we still have good reason to believe that animals will be regenerated.

To begin with, we need to be sure we’re thinking about the correct afterlife. The standard Christian approach to the afterlife is that it involves a physical New Earth in which resurrected bodies enjoy God’s physical creation for eternity (Isaiah 65:17, 2 Peter 3:13, Revelation 21:5).

This standard view can sometimes clash with the "Pop-Heaven" view held by many Christians today, in which our disembodied souls exist in a Platonic, ethereal, and purely spiritual realm outside of time and space for eternity. There are a ton of great resources exploring the history of the influence of Platonic thought on Christian consciousness, but for the purposes of this article, it’s just worth noting that Biblically speaking, eternity is a physical existence taking place on a regenerated New Earth, rather than a disembodied spiritual realm.

With the correct material view of eternity in mind, it makes sense that the entirety of God’s "very good" created order (Genesis 1:31) would be made new once evil is defeated. Indeed, Christ affirms in Matthew 17 that “all things” will be restored and again proclaims in Revelation 21 that He is “making all things new”, so it would be odd to imagine a physical New Earth in which “all things” have been made new, except for animals.

Of course, Christ didn’t die for animals the same way he died for humans. Animals don’t sin and animals aren’t made in God’s image, but at the same time, animals are very much a part of the fallen world, all of which is redeemed by Christ’s death.

Romans 8 is explicit here:

“For the creation eagerly waits with anticipation for God’s sons to be revealed. For the creation was subjected to futility … in the hope that the creation itself will also be set free from the bondage of corruption into the glorious freedom of God’s children. For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together with labor pains until now… eagerly waiting for adoption, the redemption of our bodies.”

Paul indicates here that the whole creation has been groaning in its suffering and that creation itself participates in the hope of being set free from the bondage of corruption. If all of creation is longing for redemption, we should expect all willing creation to participate in that deliverance.

This is just a short argument supporting the Biblical case for animal resurrection, but here's a longer article that provides some additional justification for those interested.

Assuming that God grants animals conscious existence in the New Earth, then the problem of their suffering is not resolved by justification but by redemption. It is not explained, but overwhelmed. Rather than defend evolution as good or necessary, the eternalist defense simply says that the pain was real, but it is not final.

Does Eternal Glory Trivialize Suffering?

Other critics might argue that this defense trivializes suffering. If suffering is ultimately "zero," why care? Why intervene? Why act ethically at all?

The answer is pragmatic and Biblical.

In many areas of life, people routinely live by one set of practical truths while accepting another set of contradictory abstract truths.

People can accept logically, for example, that solid objects are mostly empty space, yet we don’t hold our breath every time we sit in a chair hoping we don’t fall through. We’ve constructed a pragmatic mental model of the world, and even though we can logically accept that the mental model isn’t totally accurate, we still lean into our sensory intuitions because the model works pragmatically. In this case, the pragmatic model that helps us navigate everyday life takes precedence over the abstract truth.

The work of David Hume provides another example. Hume showed that inductive reasoning and cause and effect relationships are both entirely suspect. He famously argued that just because the sun has risen every day in the past doesn’t mean we can know it will continue to rise in the future. But despite accepting the logic of his own skepticism, Hume nevertheless continued to use inductive reasoning and cause and effect throughout his life to make accurate predictions about the world.

Calvinists provide yet another example – even though salvation is predestined, Christians are still called to evangelize.

Each of these cases involve a contradiction between a logical truth and a pattern of pragmatic action. Moral action is the same. Even if eternal life renders suffering metaphysically insignificant, our moral intuitions about compassion, justice, and care remain essential.

Pragmatically, these intuitions work. These intuitions help societies function, reflect divine character, and respond to Scripture’s clear call to act ethically and love universally.

The Biblical duty to alleviate suffering by caring for the poor, the widow, and the oppressed is not canceled by the promise of eternal joy – it is enhanced by it. We act morally not because of suffering’s significance, but because we are called to reflect the love and mercy of a God who redeems suffering. Just as Christians are called to evangelize even when outcomes are predestined, they are called to act ethically even when suffering is not ultimate.

In short, even though suffering is ultimately insignificant, pragmatic intuitions and Scriptural duty demand that we continue to lean into Biblical moral teaching and Christian living.

Conclusion

The Eternal Weight of Glory defense reframes the problem of evil by viewing it in the context of eternity. While suffering is real now, it becomes completely insignificant when considered against the vastness of eternal existence.

This defense is not a utilitarian calculus where suffering is merely outweighed by future bliss. Instead, it is the conviction that God redeems finite suffering with infinite bliss, which necessarily reduces the significance of finite suffering, both mathematically and experientially, to nothing.

Of course, this still doesn’t explain why evil exists per se (this is a defense, not a theodicy) but it does reduce evil’s significance to be on par with the significance of a random grain of sand on a beach in Thailand or a single hydrogen atom on the sun. We could ask why God created these things, but we’d be wasting our breath.

Despite suffering’s ultimate insignificance, however, humans are still justified in leaning into moral intuitions. In addition to clear Biblical injunctions to act morally, it’s also common for humans to accept logical truths that clash with useful intuitions. So long as the intuitions work, we should continue to lean into them.

The problem of evil is one of the most difficult challenges to the Christian conception of God, but when compared to eternity, the problem melts away. Ultimately, the Eternal Weight of Glory ensures that all willing creatures will be fully redeemed.

I don't believe suffering = evil. Evil typically results in suffering but we need much of what we call suffering to keep the world balanced. Suffering is a feature. I also like the idea that evil isn't created by God but evil is the absence or rejection of God.

And to add one more layer on this, in Physics, everything resorts to entropy. It takes energy to create order. Suffering is also largely driven by entropy. We mitigate suffering by adding energy. So, without something providing energy to create order, entropy is the natural state.

This is why I, personally, ascribe to a modified simulation theory of existence. We are instantiated in a life to grow and mature, basically overcoming entropy towards greater order. Instead of a Heaven of infinite reward, we learn lessons and return to another instantiation. In this case, the suffering is still a feature and the goal is to learn how to reduce it by reducing entropy. (Frankly, I find the idea of Christian heaven dismally boring)

I've got an essay scheduld to come out in the next month titled "Reincarnation Sounds Awesome." which looks deeper into that topic as well but sufice to say, Entropy is the foundation of physics, suffering is a form of entropy, and I think we are here to help add energy to overcome entropy.

Insightful and thoughtful take, though I have to disagree. The finitude of suffering does not diminish its value. It only diminishes its temporal significance, not its moral or spiritual significance. On the contrary, suffering is of immense value in the Christian faith. We innately feel the, as C.S. Lewis puts it, "unnaturalness" of human death and suffering. That's why it's everyone's greatest hurdle to faith. Christ specifically entered into our sufferings--he wept at our suffering. While the Glory to come will change how we view suffering, in some sense, suffering has to do with every piece of life outside of renewal.

That said, I think an important response to Alex O'Connor is the acknowledgment that most Christians get animal death wrong, viewing it as something post-fall, which brings up numerous claims on animal morality, animal souls, etc. In reality, and clear in Jewish and Catholic thought, animal death was always a part of the hierarchical created order. Lions have always been carnivorous, bees have always stung. There are many reasons for this, but the question for Alex becomes, "If animals have no souls, and no claim to immortality like humans, can they really be said to suffer?"

Very thought provoking article!