Is there a single word that sounds more ridiculous coming from the mouth of a full-grown adult than “woke”? What was originally popularized for the masses by “in-the-know” progressives has since morphed into a pejorative term describing progressives who act “in a way that is considered unreasonable or extreme”, according to Merriam-Webster.

These two understandings of woke, one positive, one negative, form two highly defined battle lines, with supporters of each definition staring each other down across no man’s land. The debate over woke has taken over the public square by force, but neither side can seem to persuade the other to take their perspective seriously.

Bishop Barron laid out the extent to which “wokeism” has dominated public discourse and zero-sum thinking in a speech at Acton University in 2023:

It might be argued that the central preoccupation of the cultural conversation in the West today is “wokeism.” This system of thought and action has rather remarkably found its way into practically every nook and cranny of our political, economic, and cultural arenas, and it’s having a massively deleterious effect on our culture. One of our major political parties has largely organized itself around defending woke ideas and implementing woke strategies, and the other major party has begun to organize itself against the same.

The centrality of wokeism to political discourse today is undeniable. The problem is, the term carries a ton of baggage and is highly polarizing. Is it just political correctness? Is it cancel culture? Is it a meaningless right-wing buzzword? Is it already outdated? Did it mean something at one point but is now hopelessly weaponized? Ask a hundred people and you’ll get a hundred responses.

Given the disagreement, talking about wokeism is no easy task. Complaining about wokeism results in an immediate loss of credibility with anyone left of center. On the right, the center-right has grown increasingly agnostic about the term, yet the anti-woke “New Right” absolutely loves the term.

Much of the New Right’s love for railing against the woke is tied to signaling in-group loyalty and identifying a common enemy. The New Right’s love of the word has already caused it to lose meaning for almost everyone else. The below graphic sums up the reactions to wokeism by political affiliation.

Depending on the audience, complaining about wokeism can signal either extreme unseriousness or a zealous commitment to owning the libs. There is no in-between. The question is, should there be? Should there be a more serious way to discuss wokeism so that the center-right and center-left can engage with the issues being raised?

The question hinges on what wokeism actually is. If it’s merely a right-wing buzzword meant to signal in-group loyalty, then maybe the center-right and center-left are correct to dismiss it. If, however, wokeism is a real movement with deeper philosophical roots, then maybe it needs rebranding.

What is Wokeism?

Plenty of authors from both the left and the right have spilled pools of ink to describe what wokeism is, where it came from, and what the implications of the illiberal forms of wokeism are. Some of those authors (in no particular order) are:

Vivek Ramaswamy: Woke, Inc.

Chris Rufo: America's Cultural Revolution

Richard Hanania: The Origins of Woke

John McWhorter: Woke Racism

Heather Mac Donald: The Diversity Delusion

Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt: The Coddling of the American Mind

Jonathan Rauch: The Constitution of Knowledge

Douglas Murray: The Madness of Crowds

Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay: Cynical Theories

Eric Kaufmann: The Third Awokening

Some of the definitions offered in these books are better than others, and there is a ton of variance between the different definitions. Many are not mutually exclusive. In general, most definitions focus either on the current effects of wokeism or the philosophical underpinnings of wokeism. My definition will be of the latter type, but I am not arguing that definitions of the former type may not also be correct.

I define wokeism as the mass popularization of a specific set of pessimistic illiberal philosophies that originated in Europe. The most proximate versions of the philosophies that caused wokeism are:

The neo-Marxist philosophies of the Frankfurt School and

The philosophies of the French postmodernists

Both of these proximate influences on wokeism have their own intellectual influences, spanning back hundreds of years to (obviously) Karl Marx himself, as well as Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Rousseau.

While there are important distinctions between these various philosophical traditions, the thread that binds them together is a deeply pessimistic view of rationalism, commercial society, individualism, progress, and the fundamental equality of mankind. In short, these philosophies represent a pessimistic broadside attack on every aspect of a classically liberal society.

These philosophies were first introduced to the U.S. in a meaningful way in two doses. First, during the 1930’s while the Frankfurt School was given asylum in the U.S. after being kicked out of Nazi Germany, and second in the 1960’s when French postmodernist ideas, namely those of Foucault and Derrida, took U.S. universities by storm.

After these philosophies first entered U.S. academia in a meaningful way, the ideas gradually seeped deeper and deeper into the public’s broader consciousness. This trickle-down process took several decades, resulting in various levels of mass popularization, such as “political correctness” and “identity politics”. Eventually the ideas were supercharged by social media in the early 2010’s, resulting in “wokeism”.

Is Wokeism Really That Bad?

Maybe this all sounds a bit hyperbolic to you. Let’s take a look at the underlying drivers of these philosophies to see why they pose such a threat to liberal democracies. As a disclaimer, the following is a crash course in intellectual history and necessarily includes some generalizations. Philosophy nerds be warned.

Let’s start at the beginning. The Enlightenment was a 17th and 18th century intellectual movement in the West that stressed the importance of reason, freedom, the centrality of the individual, and human progress. The English and Scottish Enlightenments, which the U.S. Enlightenment tradition mainly derived from, also heavily stressed the importance of political economy and commercial activity as key drivers of progress.

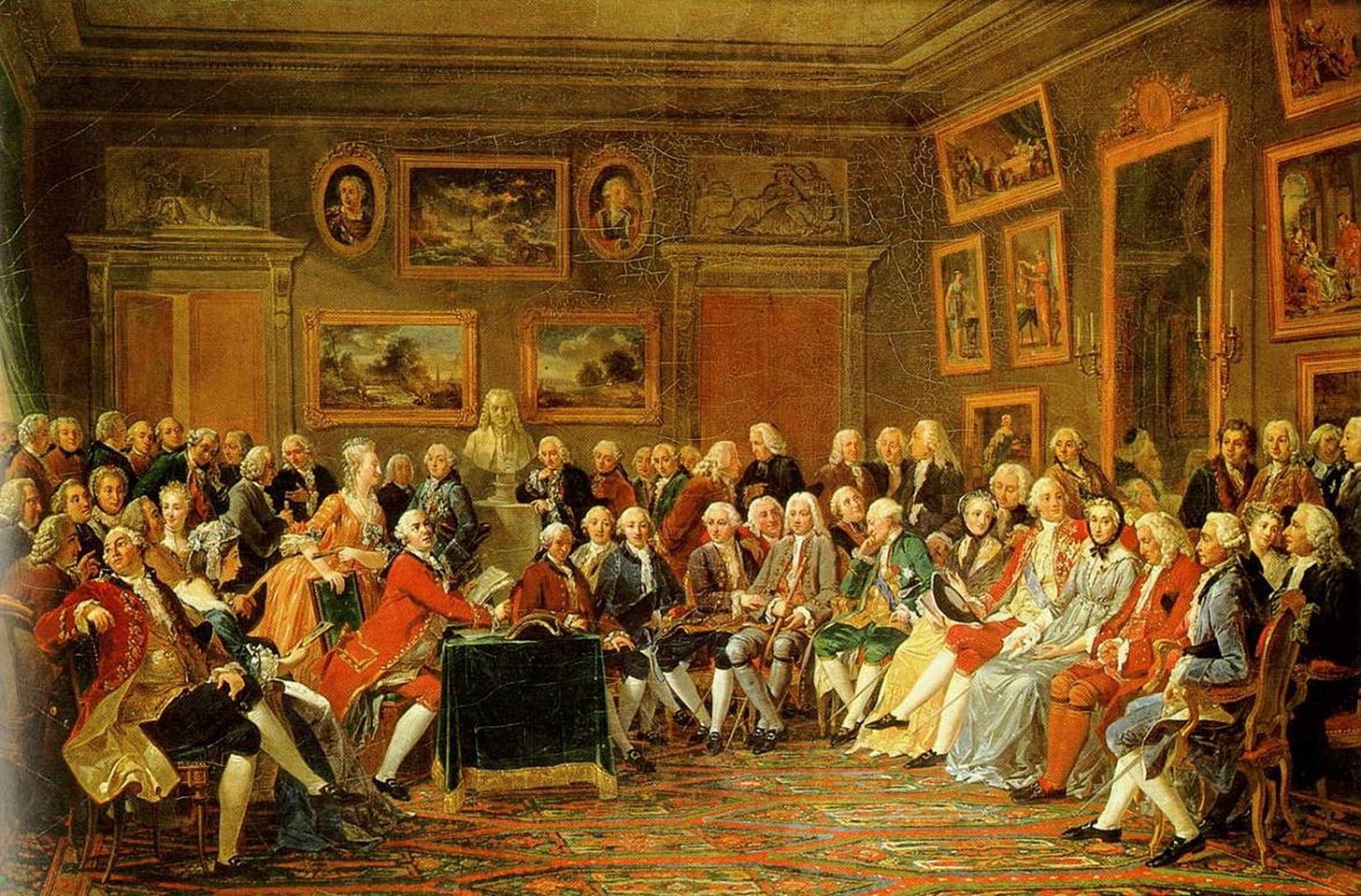

Reading of Voltaire's tragedy, The Orphan of China, in the salon of Marie Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin in 1755, by Anicet Charles Gabriel Lemonnier, c. 1812

The high-water mark of the Enlightenment was in 1787, when the U.S. Constitution was signed in Philadelphia. The U.S. founding was a uniquely theorized event, drawing heavily on both Enlightenment ideals and Protestant influences. The exact mix of these two influences on the founding is a topic of heated debate, but it is undeniable that the U.S. Constitution and the liberal democratic system that it created were products of Enlightenment ideals, namely the ideals of progress, reason, and political and economic freedom.

In dramatic fashion, the Enlightenment ended in 1793, just six years after the U.S. Constitution was signed, with the execution of King Louis XVI in France and the initiation of the Reign of Terror. The progress consensus that had been created over the past two centuries in Europe was brought to an abrupt halt by the brutality of the guillotine. The French Revolution, which was supposed to be the vanguard and new high-water mark of the Enlightenment, had devolved into barbarism, and eventually, dictatorship.

As a result of the disillusionment spawned in the wake of the French Revolution, Romanticism created an alternative way to view the world. Whereas the Enlightenment stressed reason, progress, and commercial development, Romantics stressed emotion, a fondness for the past (especially the chivalry of the Middle Ages), and a reverence for pre-industrial nature and the supernatural.

The Arcadian or Pastoral State (The Course of Empire), by Thomas Cole, 1834

In Britain and the United States, Romanticism mainly took the form of a benign artistic movement, resulting in incredible works from some of the most famous artists and writers of all time, including the Hudson River School and Byron and Shelley.

For most of my American readers, this should all be familiar territory. Here’s where things take a turn.

In France and especially in Germany, Romanticism went down a much darker path. Compared to their Anglo counterparts, the Continent’s version of Romanticism was much more intellectualized. German Romantics, reacting to the physical reminder of the excesses of the Enlightenment represented by occupying Napoleonic armies, embraced strident German nationalism, reactionary politics, and open hostility to political liberalism, rationalism, and cosmopolitanism.

In the wake of the Revolutions of 1848, which had a similar disillusioning effect as the French Revolution did for the prior generation, anti-Enlightenment feelings on the Continent continued to grow. In Britain and especially in the U.S., the Revolutions of 1848 had almost no effect. On the Continent, however, the revolutions were monumental and continued to drive anti-Enlightenment and nationalistic sentiment. For the German Romantics, much of the Romantic reverence for the past became reverence specifically for the hierarchies of the past, especially the strength and will of ancient aristocratic lineages and pre-Christian Nordic and Germanic tribes.

Racial pessimists such as Arthur De Gobineau saw commercial society and the middle class it spawned as evidence of the dilution of the superior aristocratic “Aryan” races. The British and American Romantics tended to celebrate nature and emotion. Their German Romantic counterparts instead romanticized a Nordic pagan past built on violence, conquest, and spontaneity. The cooperation and rational progress inherent in the Christian commercial societies of modernity became enemy number one. De Gobineau’s theories of Aryan supremacy were enthusiastically embraced by German intellectuals like the composer Richard Wagner, his son-in-law and Nazi philosopher Houston Stewart Chamberlain, and other members of the Bayreuth Circle.

During his earlier years, Friedrich Nietzsche ran alongside several members of the Bayreuth Circle and even shared a close personal relationship with Richard Wagner, driven primarily by a common interest in German nationalism and Romanticism. Nietzsche synthesized the historical pessimism of figures like Rousseau and Jacob Burkhardt with the anti-Christian pessimism of Arthur Schopenhauer to develop a new form of cultural pessimism that would change philosophy forever.

In a similar vein as the racial pessimists, Nietzsche’s cultural pessimism claimed that modern commercial society had devolved from a romanticized pre-industrial past. Instead of a dilution of racial purity, however, Nietzsche argued that Germanic cultural purity was on the decline.

Nietzsche blamed the weak “slave morality” of Christianity for diluting the cultural superiority and vitality of the Aryan elite. The universalizing mission of Christianity, with its focus on equality for the masses, was the engine by which the slave morality of the weak was allowed to dilute the power of the strong and the noble. According to Nietzsche, the “will to power” of the strongest in a society was evidence of the strong’s superior cultural vitality and willingness to embrace the Romantic ideals of spontaneity and violence to achieve power.

“Nietzsche’s Will to Power”, per ChatGPT. Interestingly similar to the Romantic classic “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog”, by Caspar David Friedrich. The anti-Enlightenment Romantic impact on Nietzsche was strong.

To Nietzsche, the will to power was the fundamental driver of human behavior and social structures. Nothing else mattered. Christianity’s empowerment of the weak and the many at the expense of the strong and the few put it squarely in Nietzsche’s crosshairs.

Democracy and commercial society, two natural derivatives of Christianity that similarly benefitted the many over the aristocratic few, were also frequent targets for Nietzsche.

In a dark parallel to Darwin, Nietzsche believed that the strongest should survive, not for biological reasons, but for aesthetic ones. Although Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man” wasn’t released until 1943, we can be sure of Nietzsche’s reaction had it been released earlier – contempt for it and everything it stands for.

These two new strains of anti-Enlightenment thought, one racial, one cultural, continued to fester in European intellectual circles for the following decades. These theories eventually produced a dark form of Degeneration Theory around the turn of the 20th century that reflected an increasingly anxious pessimism about the future of Europe. Thinkers such as the criminologist Cesare Lombroso, the psychologist and social critic Max Nordau, and the eugenicist and half-cousin of Charles Darwin, Sir Francis Galton, advanced pseudo-scientific theories advocating for radical levels of censorship, state repression, and eugenics in order to address the “social question”.

Against this backdrop of increasingly pessimistic social commentators, the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels gained immense popularity. Marxism now represented the most radical way to address the social question – bloody and violent revolution. No small wonder then, that Marx’s favorite quote comes from Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust: “Everything that exists deserves to perish”. Marx would get his nihilistic wish with the horrors of World War I.

Following the end of the First World War and the subsequent failure of German communism, the Frankfurt School was established in 1920’s Weimar Germany to synthesize Marxist thought with the new political and economic realties of the 20th century. The result was Critical Theory, which spawned several related strands of theory in the next few decades, including feminist theory, critical race theory, queer theory, and postcolonial theory.

Prominent names associated with this school of thought include Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse. These German neo-Marxist theorists left Germany following the rise of Nazism in the 1930’s and settled at Columbia University in 1935. Thus began the American academic radicalization that would eventually morph into wokeism.

The second wave of infection began in the 1960’s when the ideological descendants of the Frankfurt School, the French postmodernists, gained prominence in academic circles. Both the Frankfurt School and their French postmodern counterparts used critical theory to deconstruct reality and reject narratives associated with progress, optimism, rationality, and the unified and coherent individual. In their place, the postmodernists took the Marxist perspective that economic class struggle was the basis for human interaction and multiplied the dimensions of oppression to include race, sexuality, gender, and colonial past.

This antagonistic theory of social relations relied on a Nietzschean understanding of power. In this view, power is the sole end of human interaction. Therefore, western notions of rationality, commerce, language, entertainment, democracy, or anything else you can think of are really just expressions of power meant to subjugate oppressed groups. Kimberle Crenshaw's development of “intersectionality” and identity politics is directly related to the idea that shared humanity and individuality are western notions that should be dismissed. Instead, people are best understood by their relative power and their status as either oppressors or oppressed.

Other hallmarks of postmodern thought, including extreme moral relativism, the rejection of objective truth, and an extreme sensitivity to language can also be seen clearly in today’s discourse on wokeism. In short, the most common definitions of the effects of wokeism include something along the lines of an elevation of identity to the sacred, paired with extreme levels of moral and cultural relativism. These effects draw directly from postmodern and neo-Marxist perspectives.

A great article by Helen Pluckrose sums up the postmodern perspective nicely:

“Morality is culturally relative, as is reality itself. Empirical evidence is suspect and so are any culturally dominant ideas including science, reason, and universal liberalism. These are Enlightenment values which are naïve, totalizing and oppressive, and there is a moral necessity to smash them.”

The strain of anti-Enlightenment, anti-positivist, and authoritarian thought that makes up modern wokeism has been frequently traced to the Frankfurt School and the postmodernists. This line of pessimism, however, can be traced even further back to Marx, Rousseau, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche. Nietzsche’s fierce critiques of the Enlightenment and modernity, his concept of the will to power, perspectivism, and his critiques of reason all heavily influenced both the neo-Marxists and the postmodernists. Nietzsche’s assertion that “there are no facts, only interpretations” sounds like it could have been written by Derrida himself. His critiques, and the critiques of his ideological descendants, were aimed most pointedly at the primary representatives of liberal democratic Christian societies – Britain, and later, the United States – who supposedly represented everything wrong with modernity.

So Why Does This Matter?

Wokeism is not just a flash in the pan or a right-wing buzzword. Wokeism is the mass popularization of a set of illiberal ideologies that stretch back more than two centuries. The contrast between this set of illiberal ideologies and the liberal democratic foundations of the United States couldn’t be starker.

The United States was founded as the crowning achievement of the Enlightenment, under the ideal, imperfectly embodied but continuously pursued, that all men are created equal, and that through mutual cooperation and the political and economic empowerment of the individual, a more perfect union could be formed for the peace and prosperity of the nation. The great inheritances of the United States – morality and equality from Jerusalem, democracy from Athens, and the rule of law from Rome – have endowed Americans since the founding with a sense of optimism about their exceptional role in world history.

Perhaps you agree with the postmodernists that this all sounds a little naïve. The only naivety here, however, is the postmodernists’ blindness when it comes to recognizing that liberal democracies have produced by far the safest, freest, and most successful societies we’ve ever seen.

Britain’s Whig history and America’s manifest destiny and Wilsonian idealism reflect the long history of optimism that has dominated Anglo-American perspectives on liberal democracy for centuries. The Anglo-American intellectual tradition is one rooted in optimism and the prudent pursuit of ideals. These optimistic perspectives on both the Enlightenment and the political and economic institutions that derive from Enlightenment ideals stand directly opposed to the cultural pessimism of Nietzsche and his ideological heirs.

Optimism vs. pessimism; progress vs. declinism; the pursuit of ideals vs. nihilism. These are the battle lines drawn between the Anglo-American tradition and the Continental Nietzschean postmodern tradition. Since wokeism is the continuation of a centuries-old philosophical system that directly opposes liberal democracies, it is in the interest of both the center-right and the center-left to resist this ideology. To do so, wokeism will need a rebrand. A few options have been provided, such as Tim Urban’s Social Justice Fundamentalism or Eric Kaufmann’s Cultural Socialism, but I think more can be done to come up with a serious yet catchy rebrand for this strain of thought. More ideas on this later.

Conclusion / TL;DR

Wokeism represents the mass popularization of a set of illiberal and pessimistic philosophies that date back to the 18th century. These anti-Enlightenment philosophies rooted in the cultural pessimism of Nietzsche stand directly opposed to the American intellectual tradition. American historical narratives since the founding have been characterized by a fundamentally optimistic and progress-oriented Enlightenment ethos that revels in the prudent pursuit of ideals. Holding ideals is not naïve. Thinking you can dispense with ideals without descending into hell, however, is.

To rediscover American idealism and push back against the pessimism of a postmodern worldview, wokeism needs to be understood by both the left and the right for what it is – an existential threat to liberal democracy. The seriousness of the threat that these illiberal theories pose to liberalism does not match the seriousness of the word “woke”. It’s a silly word. A rebranding of wokeism is needed so that both the center-left and the center-right can discuss the threat of illiberal postmodernism seriously.

Sources

Herman, Arthur. The Idea of Decline in Western History. Free Press, 1997.

Bishop Robert Barron: The Philosophical Roots of Wokeism | Acton Institute

Helen Pluckrose: How French "Intellectuals" Ruined the West: Postmodernism and Its Impact, Explained - Areo (areomagazine.com)

S Peter Davis: The Real Origin of Woke - by S Peter Davis (substack.com)

Lewis Waller: Wokeism - Then & Now (thenandnow.co)

Others linked throughout the post

Interesting article. I agree with most of your content, but I am not sure that I understand why you believe “Wokism needs a rebrand.” Many intellectuals have tried to rebrand the movement (many of which you list in the article), but none have yet succeeded.

It seems that the problem is that the Center-Right does not take the threat seriously, while the Center-Left takes the “nothing to see here” philosophy and often supports implementation of Woke ideology. I am not sure a rebrand is necessary.

I do not think the term “Woke” is silly. It is the idea itself that is the problem. The entire system of thought is fundamentally a universal acid of all necessary ideas and institutions that promote material progress and human flourishing. Calling it by a different name is just going to cause confusion among potential opponents.

The Woke are masters at the manipulation of language that make themselves appear to be in favor of one thing while they actually are the opposite. This is particularly useful at making the Center-Left their allies and making the Center-Right belief that they are harmless idiots. They are very careful to dodge any attempt to give them a name.

I believe the Left are the latest manifestation of the Totalitarian Left. If a rebrand is necessary, maybe that is the best term.

I have more here:

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/understanding-diversity-equity-and

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/the-rebirth-of-the-totalitarian-left

Doesn’t really require that many words and references to who wrote what in the past.

Wokism: If you do not conform to the very, very few in society, then you are everythingphobic.

Pretty much explains it.