What Christianity Can Teach Us About Polarization

How the most successful movement of all time harnessed a simple and compelling narrative to change the world

The depolarization movement is currently struggling to gain meaningful momentum. Even though 87% of Americans view polarization as an existential threat and 79% of Americans are willing to help reduce social divisions, the number of Americans who have heard of the depolarization movement, much less gotten involved, leaves much to be desired.

To gain some inspiration, depolarization organizations should look to learn from arguably the most successful movement of all time – Christianity.

Today, Christianity is the world’s most popular religion, claiming 2.4 billion adherents globally. In 2050, Christianity is expected to grow to 2.9 billion adherents and make up 31.4% of the global population, slightly more than it makes up today.

The growth of a small Jewish sect in first century Judea to the world’s largest and most well-established religion is no small feat. The feat is made all the more impressive considering the fact that Christians were sporadically and viciously persecuted for the first three hundred years of the religion’s existence.

On top of its power to grow, Christianity has also demonstrated remarkable staying power, with its projected 2.9 billion adherents in 2050 living almost 200 years after Nietzsche famously declared that God was dead. It seems the reports of God’s death have been greatly exaggerated.

What can those who are looking to start a movement learn from one of the most successful movements in history? There are tons of answers, but I’ll explore two that are relevant to the depolarization movement today. I’ve argued before that the two keys to a successful depolarization movement are to find a message that is simple and compelling. The Christian message has an interesting twist on these characteristics that the depolarization movement should seek to emulate.

1. A Simple Message

The first key to a successful movement is lowering the barriers to entry for new members while ensuring that there are subsequent barriers to continue climbing for existing supporters. Christianity is the perfect example.

On the one hand, the Christian message is one that can be distilled to a single simple phrase: Jesus loves you. On the other hand, the Christian message is also infinitely complex, as intra-Christian debates on everything from the nature of the trinity to eschatology to predestination have raged for over 2,000 years amongst theologians who have devoted their lives to studying these topics.

This “layered complexity” is one key to creating a successful movement. Movements need both a low-complexity entry point for new initiates as well as increasingly complex subsequent layers to keep members engaged.

To prove the point, let’s consider two very different works of literature:

The Very Hungry Caterpillar is undoubtedly a great piece of children’s literature, but coming in at 224 total words, its complexity is minimal. Tolstoy’s War and Peace, with 560,000+ words and 1,400+ pages, is considerably more complex. Which piece of literature is more likely to create and sustain a mass movement? Neither.

While The Very Hungry Caterpillar is easily accessible to all and can be easily digested (no pun intended), it isn’t complex enough to sustain the interest of the same audience for years or decades. War and Peace, on the other hand, is anything but approachable. Although its complexity has allowed for study and debate for over 150 years, its length renders it inaccessible to most.

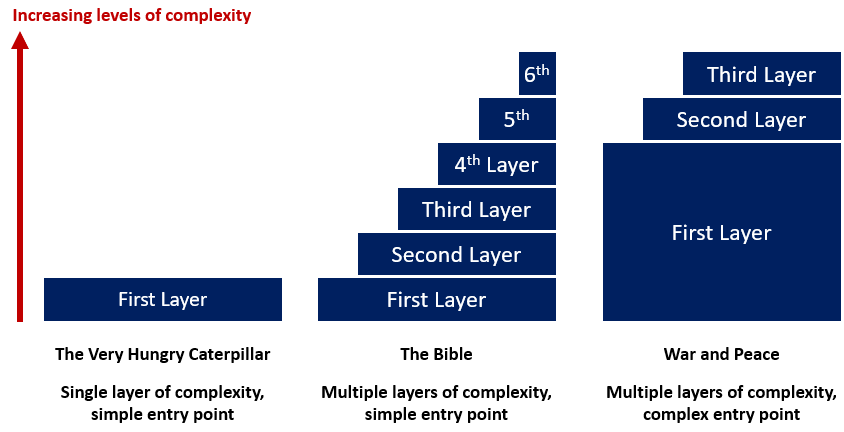

Here's a simple graphic explaining the layered complexity continuum:

The level of complexity increases with height. The Very Hungry Caterpillar has a low level of complexity to begin with and doesn’t have any additional layers of complexity. War and Peace’s first layer, on the other hand, is almost at the top of the complexity scale. The high complexity of the first layer makes War and Peace a daunting piece of literature.

The Bible, on the other hand, is a document that can be distilled down to a single simple verse: John 3:16. Despite that simplicity, scholars will also devote their lives to studying and debating a single book or chapter of the Bible. This simple entry point with additional layers of subsequent complexity creates the ideal “stair-stepped” pattern in the graphic above. Layered complexity allows for a simple entry point with subsequent depth. This layered complexity is key to a movement’s ability to attract new members and sustain the engagement of older members.

If the Christianity analogy isn’t doing it for you, consider Marxism instead. Marxist theorists have devoted their lives to studying the writings of Marx, and the complexity of his writings has inspired endless debate. The Communist Manifesto’s call for “Workers of the world, unite!”, however, is simple enough to be understood and repeated by all. This layered complexity is the key to building and sustaining a movement, even if that movement ultimately collapses under the weight of its own contradictions (Mr. Gorbachev…). The centuries-long strength of the Marxist movement, despite its contradictions, is proof that layered complexity is an extremely powerful tool for building and maintaining a movement.

Currently, the depolarization movement is firmly on the War and Peace end of the complexity spectrum. There are plenty of incredible resources out on polarization right now, including this great summary of the latest polarization research by Rachel Kleinfeld, as well as plenty of books covering polarization from a variety of angles.

As great as these resources are, they are written for largely academic audiences. Even when they aren’t, they certainly aren’t written for extreme partisans. Additionally, many polarization experts point to 15 or more different causes of polarization, which tends to have the effect of losing the interest of an audience, or worse, inspiring hopelessness.

To create a successful movement, depolarization messages will need to be vastly simplified so that they can be quickly and easily disseminated on the street or around the dinner table. As Ronald Reagan once famously said, “All great change in America begins at the dinner table”. Right now, the reason no one is talking about depolarization strategies at the dinner table is because they are too complex. The depolarization movement desperately needs a simpler entry point, akin to “Jesus loves you”, in order to truly engage the tens of millions of people needed to launch a movement.

2. A Compelling Message

The second key piece of effective messaging is a compelling message. How compelling? At least as compelling as the alternatives.

The Jewish citizens of first century Roman Judea had a long history of “us vs. them” struggle. From the initial Exodus from Egypt, to the Iron Age wars against the Philistines, Edomites, Moabites, Ammonites, and others, to the conquest of the Kingdom of Israel by Assyria, to the conquest of the Kingdom of Judah by Babylon, to the Persian conquest, to the Greek Hellenistic conquest, to the Roman conquest, the Jews of first century Palestine were no strangers to good vs. evil struggles of apocalyptic proportions.

In fact, this good vs. evil, us vs. them tribal struggle had been the norm for most of human history, and tribal identities are amongst the most powerful motivators we know of. So how was Christianity able to spread a new message within both a Semitic and Greek culture that had been steeped in millennia of tribalistic us vs. them thinking?

There is a common, idealistic idea that a message that focuses solely on the “us” or the “good” will be a more powerful message than an us vs. them or good vs. evil message. Messages like “love wins” or the older “peace and love” aspire to transcend the need for a fight against evil by focusing solely on the good. By offering people a message of hope, togetherness, unity, and love, the thinking goes, we can build bridges towards a brighter future. Much of the depolarization movement is filled with this type of messaging.

Core to this idealistic line of thinking is the example of Jesus himself. Amidst the multitude of good vs. evil narratives percolating in first century Judea, Jesus came along and preached a message of peace and love, which triumphed over all the other messages.

The problem with this view is that Jesus actually spoke about hell more than heaven. Contrary to our modern whitewashed view of Jesus’ message, Jesus was hyper-focused on evil. The key, truly brilliant, Christian insight was not to disregard evil entirely, but instead to replace the evil of the other with the evil of the self.

Good vs. evil narratives are extremely powerful, so to truly compete with these narratives, a new narrative must define a new evil, rather than dispense with the concept of evil entirely. Due to negativity bias, we know that the negative is psychologically more powerful than the good. A message that solely focuses on good, therefore, will simply not compete with a good vs. evil narrative. Fighting evil galvanizes action much more effectively than simply rallying for good solely for the sake of the good.

Early Christianity did this masterfully by preaching a good vs. evil message that focused on the evil of personal sin rather than on the evil of the tribe next door or the tyrannical powers that be. The Christian ethical revolution was the message that evil does not lie with them, but with you.

By internalizing evil and focusing on the individual rather than the other, early Christianity maintained the urgency of fighting evil while simultaneously reducing the need to fight the other. The key to the success of the Christian message was not to preach only about the good, but to redirect feelings about the bad towards new ends, in this case, resisting personal sin.

For a more modern example, think about Martin Luther King Jr. It can be easy to whitewash MLK as an idealist who focused solely on hope, love, and a positive future where his descendants would be judged based on the “content of their character.” This view of MLK’s message does a disservice to the very real evils he was actively preaching against – injustice and inequality. These evils were antithetical to the entire idea of what it meant to be an American. Without focusing on these evils, MLK’s message would not have been nearly as impactful. MLK appealed to the good, but that good was contrasted with very real evils. MLK did not simply appeal to the good solely for the sake of the good. A focus on fighting actual evil is key to a galvanizing message.

Currently, the vast majority of depolarization messaging focuses solely on the good. “Bridge-building”, after all, is about unity, togetherness, and tolerance, right? Unfortunately, when the majority of the messaging on the left involves a narrative along the lines of, “if the right gains power they’ll destroy the planet, roll back protections for women and minorities, and enrich the wealthy at the expense of the poor” and the right hits back with messaging along the lines of, “if the left gains power they’ll destroy the economy, ostracize and marginalize your faith, and sexualize your children”, can an appeal to civility and nuance really hope to compete?

Instead, the depolarization movement needs to take a page out of Christianity’s playbook and redefine and attack evil, rather than ignore it. The most important question the depolarization movement should be asking itself right now is, “What are we fighting against?” If the answer is not as compelling as the “evils” pushed by the left and the right, the movement will continue to flounder. When it comes to building a movement, combativeness is a necessity, not an option.

Putting it all together

So, what kind of a depolarization message fits the simple and compelling standard? In my opinion, the Negativity Thesis, the idea that negativity bias is the sole root cause of polarization, is an excellent candidate.

The idea is simple in that it reduces the causes of polarization down to a single cause – our addiction to negativity. At the same time, this simplification is really an entry point to an extensive and complex literature on polarization that can be studied for a lifetime. To achieve layered complexity, the depolarization movement is in desperate need of a simplification of the problem. The Negativity Thesis supplies that simplification.

The idea is also compelling in that it identifies an evil to be resisted, rather than solely appealing to the good. Like Christianity, the Negativity Thesis replaces the evil of the other with a personal evil that each of us needs to contend with – our personal addiction to negativity. This addiction is evil because it warps our worldview and causes a host of negative downstream effects, including poor mental health outcomes, pessimistic grand narratives, poor policy decisions, and of course, political polarization.

By spreading the more combative message that each of us individually is the problem, rather than the tribe next door or the powers that be, the depolarization movement can finally offer an evil to fight against that rivals the “evils” pushed by the left and the right.

The current depolarization messages that merely appeal to the good or that fight against trivial evils (such as primary election reform or niche voting mechanisms) will continue to struggle to galvanize meaningful support. To truly inspire meaningful change, the depolarization movement will need to redefine and actively combat an evil. The Negativity Thesis defines that evil as our subconscious addiction to negativity.

TL;DR

The success of Christianity as a movement offers great insights into how other aspiring movements can become successful – namely by focusing on messaging that is simple and compelling.

First, simplicity is needed because it provides a low-complexity entry point for new supporters of the movement. Layered complexity is then needed to keep members engaged. The Bible’s simultaneous simplicity and complexity is a good example.

Second, a compelling message is needed that can truly compete with alternative good vs. evil narratives. Messages that solely focus on the good will not be as successful. Christianity’s focus on the evil of personal sin rather than the evil of the other is a good example.

The Negativity Thesis is a good candidate for a simple and compelling message. It simplifies the causes of polarization down to a single cause, and it redefines the evil of the other as the evil of our personal addiction to negativity.

You are right about the numbers of Christians. And about 17% to 23% of the electorate in the US is libertarian according to Gallup. And yet they have no power and no real representation in government because the two main parties are those funded by the wealthy elite. Unless they got equivalent funding, they would go nowhere. After 300 years, Christians had grown to 10% of the population. Thanks to Constantine, they became 60% in a very short time. I think we do have the same information and choose to interpret it differently. That's what I like about substack, intelligent conversations.

Under your logic, the people in US suddenly divided themselves into two factions and they drive the political parties. Except that studies like the one from Cambridge University showed that over a 20-year period, almost all of the laws made by both political parties served wealthy special interests (businesses), not general special interests, nor the people. That would seem to be evidence that the political parties serve those who fund them, those who vote in the money election before the general election when we get to vote for the two people they have already chosen for us. I think they tell people what to believe through the media that they control rather than listen to the people. Of course, we are both speaking in generalities because specific situations can go either way.

But this is what life is all about. We each take in information and make a judgment call about what it means, and what is true and what isn't. And those are largely determined by our beliefs, which come from experience but also largely from indoctrinations that we are not even aware of. I've spent many years trying to surface those beliefs and examine them to consciously choose those that I want. But it's almost impossible to live outside of illusion because reality exists in our interpretations. And we each share our opinion on substack! 😊

Personal beliefs aside, I would be very interested in your feedback as to whether you think my new design for two primary government processes would yield better results for the people, or not, if you have the time to check out End Politics Now.

Interesting thoughts and metaphor. Here's an alternative and perhaps more negative interpretation. I'm not sure either one is correct or wrong. But here's something to consider.

The Christian movement was mostly underground and didn't really take off until Emperor Constantine of Rome made it the official religion and promoted it. Marxism only became powerful after it was backed by the wealthy elite of the time as Lily from a Lily Bit has done such a great job of explaining multiple times. I spent 2 years researching and writing a solution to the political divide. In looking for a root cause, it was clear to me that the divide is created by the political parties to differentiate themselves as other large businesses do. They want you to vote for the party based on ideology, not the candidate. Therefore, in all three cases it was the power, money, and influence behind each movement that made it successful.

My solution, a Collaborative Democracy, would not only solve the divide but it would give better national results and give everyone a voice. The major parts have been tried around the world and demonstrated to be better than current political processes. And yet, few people are even willing to read it, much less support it. It seems everyone wants to profit by talking about the political divide, but few want to actually solve it. Without a key influencer supporting my movement, it's clear that it will go nowhere. EndPoliticsNow.com